13 July 2022

Commission of Inquiry

PO Box 12264

George Street Qld 4003

Dear Commissioner,

Sisters Inside and the Institute for Collaborative Race Research welcome the opportunity to provide the following joint submission to the Commission of Inquiry into Queensland Police Service responses to domestic and family violence. Aspects of this submissions have been taken from our submissions to the Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce (‘the Taskforce’). We direct the Commissioner’s attention to these submissions, which deal with broader issues relating to women and girls’ experiences within the criminal legal system but ask that this submission be considered independently. It provides greater detail about women and girls’ experiences of the Queensland Police Service (QPS).

In this submission, we use personal quotes from interviews we conducted with women who have experienced DFV victimisation. They consent to their anonymised stories being used here.

About Sisters Inside and the Institute for Collaborative Race Research

Established in 1992, Sisters Inside is an independent community organisation based in Queensland, which advocates for the collective human rights of women and girls in prison, and their families, and provides services to address their individual needs. Sisters Inside believes that no one is better than anyone else. People are neither “good” nor “bad” but rather, one’s environment and life circumstances play a major role in behaviour. Given complex factors lead to women and girls’ entering and returning to prison, Sisters Inside believes that improved opportunities can lead to a major transformation in criminalised women’s lives. Criminalisation is usually the outcome of repeated and intergenerational experiences of violence, poverty, homelessness, child removal and unemployment, resulting in complex health issues and substance use. First Nations women and girls are massively

over-represented in prison due to the racism at the foundation of systems of social control. The Institute for Collaborative Race Research (ICRR) is an independent organisation, not tied to the institutional interests of any university, association, or academic discipline. Their primary purpose is to support antiracist, anticolonial intellectual scholarship which directly serves Indigenous and racialised communities. ICRR seeks to create deeper engagement with crucial political questions in an institutional context not dominated by whiteness. Its members are invested in activist, community- based scholarship and communication on race, colonialism, and justice. ICCR provides specialised additional support for those engaged in disruptive interdisciplinary research, sustaining a network of established scholars, early career researchers, students, activists and community members who collaborate in the interests of justice.

Executive Summary

The police are perpetrators of racial and gendered violence. In this submission we demonstrate the role of the QPS in maintaining broader systems of violent abuse that include and facilitate domestic and family violence (DFV). In Queensland, the QPS does not police Indigenous and racialised communities through consent but through control. Their relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women is particularly coercive, hierarchical and racially violent.

In line with best practice approaches to domestic violence, we centre the truth of the victims of abuse: Black women. If the Commission also does this, it will see a very different picture of the QPS. The Commission can then begin to understand the growing crisis of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander incarceration and victimisation, and perceive the ways in which the QPS have exacerbated this crisis.

Like domestic violence itself, police violence covers a spectrum. It moves from symbolic harm such as racial stereotyping to direct, fatal physical violence. Together these forms of violence create a matrix that entraps Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Exactly as with DFV, the most foundational violence is the fracturing of trust and reality that takes place when you are harmed by those whose duty is to care for and protect you.

In this submission we outline police violence along this spectrum, starting from the stereotyping that positions Indigenous women as criminals. We then outline the way they are trapped by interlocking state systems of control including prisons and child removal agencies, and finally examine the direct physical violence they experience at the hands of the state, or which the state refuses to see.

The submission is structured in the following sections:

1. Criminalisation: ‘She was asking for it’

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who experience domestic violence are

overwhelmingly criminalised by police and treated as perpetrators rather than victims.

2. Entrapment: ‘He did it because he likes you’

A superficial narrative of Black women’s victimhood justifies police intervention, but the QPS brutalises these women in the name of their own protection. They experience the fracturing of reality that comes with not being believed.

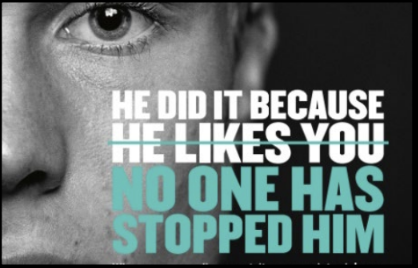

3. Murder: ‘She’s just overreacting’

Even the most direct physical harm to women caused by the QPS and the state is minimised or denied entirely. Confronting the reality of QPS abuse is essential to validate victims and find new approaches to DV.

Because there is ‘No Excuse for Abuse’,¹ we urge the Commission to examine the outcomes of police action and inaction, rather than their intentions or the justifications they provide.

We already know that First Nations women are massively over-represented in the criminal legal system; they are more likely to be arrested, charged, detained and imprisoned on remand for the same offences, and are less likely to receive a non-custodial sentence or parole, than other women.² Over-policing is to blame – but the cause of this has to be named for what it is: racism. In the settler- colonial state, police have historically been the mechanism used to control, dispossess and harm Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.³ Racism in the QPS therefore represents a continuation of colonial values implicit in the organisation since its inception. The 1,700 current or former Queensland police officers who were revealed to be members of a private Facebook page which featured extensive racist, sexist and homophobic posts demonstrates that these values are alive and well.4

Conclusions

Therefore, the police cannot be the solution to the crisis of domestic violence. Addressing superficial issues of police ‘culture’ will not change their status as perpetrators of violence. Instead, as the Australian Government domestic violence campaign states, we must ‘Stop It At The Start’5 and defund the police in relation to DFV. Any proposed solution must be evaluated against the following criteria:

Does this proposed solution expand the authority of the police and the state over women’s lives, especially over the lives of First Nations women? Does it increase the resources allocated to police in the name of that authority?

If the answer is yes, then this proposal will reproduce and increase violence.

This Commission of Inquiry has the opportunity to break the following cycle: apparent concern for violence against Black women, extension of state authority in the name of protecting these women, increased surveillance and control over these women’s lives, and a subsequent intensification of the violence that was ostensibly the subject of concern. It can do this if it centres the voices of Black women and recognises the racial violence they experience at the hands of the state. We must stop this violence where it begins and return control to women who experience DFV.

1. Criminalisation:

‘She was asking for it’

DFV and criminalised women

The evidence is overwhelming: criminalised women and girls are almost always survivors of violence.6

In turn, victims of DFV are routinely criminalised. The QPS is the most notable agent of this criminalisation. It is very common that the first encountered of DFV victims with police leads directly to the wrongful identification of these women as perpetrators, to assaults by officers, to the removal of children, to imprisonment and/or to further subjection to DFV. Cross-applications and DVOs have been shown to be often extensions of the abuse perpetrated by men against women; we consider the QPS is complicit in this abuse by wrongly supporting these cross-orders. 7

The intersection of DFV victimisation and criminalisation is particularly clear when considering the most intensively criminalised women and girls – those currently incarcerated. Repeated studies have found that:

• Up to 98% of women prisoners had experienced physical abuse;

• Over 70% have lived with domestic and family violence (DFV);

• Up to 90% have experienced sexual violence; and

• Up to 90% have survived childhood sexual assault.

In testimony to the Queensland Crime and Corruption Commission, the General Manager of the Brisbane Women’s Correctional Centre (BWCC) recently acknowledged the very different profile of women prisoners compared to men and the central role of trauma in these women’s lives:

… 80 per cent of women that come to gaol, or more, are victims before they’re perpetrators.

It’s just a different environment… (Darryll Fleming)9

Similarly, almost all girls in children’s prisons have been sexually assaulted.10 The vast majority of criminalised women have been routinely denied their most basic human rights – first in the wider community, then in prison.

QPS officers called to attend DFV situations often do not believe the allegations of these women and girls, and further criminalise and punish them because of this interaction with police. The legitimate fear that this will occur already prevents women from reporting violence to the police.

The following story was recounted to a Sisters Inside worker by a woman – Samantha* – who had a long history of sexual violence victimisation. She received a 5 year imprisonment sentence for fraud offences. Upon her release from prison, she experienced violence in a new relationship:

When the relationship broke down he came to collect his things and was physically violent towards me, he held me against a wall with one hand around my throat, and one arm across my body and arm. My sister was there and so was his friend. My sister called the police and they made me give him his property but did not provide any protection to me. The police told me that it was all sorted and that he was not pressing charges. I was shocked and told them that he had attacked me. They dismissed me and left. Two days later he was still sending my abusive texts and bruising had come up all over my neck and arms so I returned to the police to press charges and get a protection order. I showed the police woman the messages, and she advised there was little she could do as the officers who came after the assault had listed me as the aggressor as he had told them I had refused him access to my apartment to collect his things and that I had been to prison. As she looked at the extremely visible bruising across my neck, she told me that it was his word against mine, and that I had been in prison and he had no criminal history. If he pressed charges also it may affect my suspended sentence. She advised that they could not do anything further. I will never go back to the police for help again. The police have shown that they do not believe me because of my criminal history.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women and Girls

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women “are victimised at alarmingly high rates compared with the wider community.”11 This fact should elicit particular care and concern from the QPS for these women’s experiences.

Nationally, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are 32 times more likely to be hospitalised due to family violence than non-First Nations women, 10 times more likely to die due to assault, and 45 times more likely to experience violence.12 Indigenous females are five times more likely to be victims of homicide than non-Indigenous females, and are more likely to be killed by strangers. 13 Additionally, “[t]here is substantial evidence to date showing that Aboriginal women also suffer from levels of sexual violence many times higher than in the wider population.”14

Yet, rather than the QPS paying careful attention to Indigenous women’s needs as victims in DFV situations, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander victims experience the QPS not as protector but perpetrator. The QPS routinely racially stereotypes these women as criminal and dysfunctional. Rather than being protected from existing violence, they are subjected to new forms of racial violence at the hands of the state – via police assault, charges, stereotyping, disregard, incarceration, and child removal. Naming victims as perpetrators is a form of violence in itself, which directly violates and delegitimises women already suffering harm from DFV.

We agree with the statement by Nancarrow et al that ‘racism, poor relationships with local communities, misogyny, and the patriarchal culture of the police service’ are to blame for the routine misidentification and criminalisation of women and girls in these situations.15 White women may sometimes be accorded the position of legitimate victim, but this position is not available to Black women. Blackness is sufficient condition for a woman to be viewed as a perpetrator, and as deserving of the violence she experiences. This is directly demonstrated by statistical evidence: a 2017 review of domestic and family violence related deaths in Queensland found that almost half of the women killed had been identified as a respondent to a DFV protection order on at least one occasion. In the

case of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, that number rose to almost 100% of deceased women recorded as “both respondent and aggrieved prior to their death.”16

Hannah*, an Aboriginal woman also supported by Sisters Inside, was the victim of extensive domestic and family violence throughout her life, including sexual abuse by her father as a child and at the hands of two different intimate partners as an adult. She told us that in one instance where she had suffered serious physical violence at the hands of her ex-partner and his grandson, the police who attended the scene “threw me down like I was some animal” with enough force that it “broke my glasses”. She was then handcuffed before being transported to hospital. She was identified as the perpetrator: “they took that side…they didn’t even want to know what happened from me, my version”. Further, she told us that she wasn’t allowed to have anyone see or talk to her in the watch house. She said this was just one of multiple occasions where she was abused by police: “when you’re Black you got the bad ones; the officers that will treat you like nothing: throw you around, handcuff you tight, whisper in your ear…every chance they get with an Aboriginal person.” In the end, police and courts incarcerated Hannah twice as a direct result of domestic violence relationships where she was the victim.

2. Entrapment:

‘He did it because he likes you’

Once Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children encounter the QPS and the criminal legal system, this system ensnares them in a system of direct and indirect violence which is incredibly difficult to escape. This experience can be likened to that of coercive control – a focus of the Taskforce. 17

In this context, we must pay very careful attention to the construction of notions of ‘victimhood’ in relation to Indigenous women and children. An abstract and racialized narrative encompassing Black women’s victimhood justifies police and state intervention into their lives. Yet when confronted with actual individuals, the QPS and wider society rarely sees these women as legitimate victims who do not deserve their suffering. This is the result of the long-standing colonial practice of denying Black women’s humanity in ways that legitimise their dispossession and violation.18 Trapped by racialised constructions, Aboriginal women can never attain actual victimhood. Instead, they are brutalised by the police and criminal legal system in the name of their own protection. Indigenous women experience the fracturing of reality that comes from being harmed by those who are meant to protect you, and from the wider world refusing to believe that this harm is taking place.

This entrapment involves collusion between the individual perpetrators of DFV and the QPS. Survivors of DFV observe the performance of gender and racial sympathies and solidarities – they know that white male QPS officers will side with white male perpetrators. One woman that Sisters Inside supported, Wendy*, felt that police did not take her suffering seriously due to a masculine culture of ‘mateship’ between her partner and the male police officer that would attend the incidents. She felt

that her distress was treated as a mere annoyance by this police officer:

The fighting got so bad that I started calling the police – in total 17 times. We both ended up taking out DVOs on each other. I would be the one who was taken away or ordered to leave every time the police came because it was his house. They would always chat to him like he was a mate and would always take his side of the story over mine. A Constable once said to me “if you don’t stop making these calls, you’ll end up in jail”.

Sarah*, another woman Sisters Inside supports, described police as having a ‘patronising’ response and taking no action at all when she reported that her partner had breached a DVO. Sarah said the police emphasised the financial costs of opening a domestic violence case. Further, she noted that when she reported being routinely strangled by her partner to a senior police officer, “he asked ‘did that happen during sexual experiences?’…I thought what the hell does that have to do with anything…I

don’t know how that helped for him to ask that”. Sarah said this experience made her realise “you’re supposed to be able to trust authority and people in that position and it just doesn’t go like that”. QPS’s tolerance of sexism is evidenced by their failure to sack any of the 84 front line police officers who are DVO respondents.19

Similar accounts have been recorded in the extensive research conducted on this topic. For example, an Aboriginal woman explained the racialised basis of policing to Nancarrow et al in the most comprehensive Australian research on this issue – the Australian National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) study: “I was already convicted in their eyes I know because that’s how they treated me, and as a black woman against the white man too they—nobody wants to hear your story, they’re going to believe the white man”.20

Crucially, this solidarity is not the result of misguided police culture or ignorance, but a long-standing practice of complicity between the state and settlers in relation to violence towards Indigenous people. This complicity creates a culture of impunity that facilitates DFV towards Indigenous women and the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women more generally (see the following section).

There are several ways in which entrapment may manifest, for example, when Indigenous victims are arrested for outstanding warrants for minor offences or unpaid fines, are incorrectly identified as the perpetrator of violence, or when police escalate their interaction and the victim receives police- interaction charges (such as ‘obstruct’ or ‘assault’ police) as a result. As the Commissioner would no doubt be aware, the latter scenario ended in tragedy for Tamica Mullaley. These interactions may also

result in the woman being breached on a suspended sentence, bail, or community-based order and sent to prison. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women report being afraid of going to the police following violent assault due to the fear of dying in custody if arrested.

Sisters Inside has worked alongside many First Nations women prisoners from remote communities who have called on police for assistance with a family violence situation and have instead been issued a domestic violence order (DVO). A significant number of women will then breach these orders, for example, when the order affects their ability to care for their children or leaves them homeless. Our direct experience and the available evidence both demonstrate that breach of DVOs is a leading cause for women’s imprisonment in Queensland.21

Sisters Inside have first-hand experience of seeing girls and young women being forced into the child protection system and isolated from the support of their family and community when they report being a victim of violence, particularly sexual assault. This is viewed as punishment by the state for reporting violence. Further, mothers and carers are at risk of being put on notice to child protective services by inviting police into the home when reporting DFV incidents. 22 Mothers routinely tell Sisters

Inside that they put up with violence for long period of time because of the very real fear of the state taking away their babies.

Tracey* also told us that the risk of criminalisation while she was on bail was used against her when she was a victim of rape by her former partner:

Even though I was ordered not to see my ex-partner, he came to the house I was living in…he came into the bedroom where I was sleeping and raped me. I was crying the whole time and couldn’t believe what was happening. He just got up and left after he was done. I went to the police about what happened, and they told me that it probably wouldn’t hold up in court, but nonetheless they went and arrested and interviewed him. He told them I’d been meeting him in secret in breach of my bail and had lied to the police. They believed him and told me that I had no case in court, so I just dropped it. I felt so helpless and hopeless. I was the one always getting punished and he got away with just everything

It’s Not a Bug, It’s a Feature

The hostile and coercive relationship between the QPS and Indigenous communities is enduring. It is not the result of an unfortunate police culture or the individual ignorance of officers. Rather, it is fundamental to the origins of the QPS, which has always policed racialised communities differently to white communities. The QPS works for white communities, with their cooperation and consent, to offer them protection and facilitate their occupation of this place. In contrast, QPS’ relationship with Indigenous communities has always been violent – these treating these communities as a threat to be violently managed. The police have been directly involved in dispossession, frontier killings and complicity with white crimes against Aboriginal women. This is why we say that QPS polices racialised communities through control rather than consent. Coercive racialized policing is as real in a DFV context as in every other context – in fact, DFV policing is freighted with the additional history of the

race-based sexual violence that characterises Queensland history.

Historically, Queensland is characterised by an intense frontier culture, violent policing practices and a racialised sexual economy centred on the trade of opium in pearling and other industries.23 Aboriginal women are subject to specific and distressing tropes of sexual availability that have rendered them always consenting and unable to be the worthy victims of sexual and other violence. Aboriginal women are regularly seen as victimised by Aboriginal men, but in fact research into

historical and contemporary colonial relations show that mass sexual violence by white men toward Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women was central to colonisation. 24

The police have been complicit in this, actively participating, refusing to prosecute white perpetrators and reproducing narratives about Indigenous women’s alleged sexual availability and dysfunction: “[t]echnically, killing Indigenous people was unlawful, but the police, the courts and the government did not act.” 25 Extreme sexual violence and murder were acceptable and un-prosecuted. Police were also direct perpetrators of racial violence; the earliest police in the Queensland area were Native police, specifically tasked with dispossession and violent ‘dispersal’. 26 The Native Police in Queensland

operated in “the context of lawful racial violence that pervaded the Australian colonies at that time…Native Police camps were opened, closed and shifted as the frontier of settlement moved northwards and westwards.” 27

There was a strong sense of solidarity amongst white policemen, and between police and colonial society; “[t]hey could expect hospitality, the sharing of information and protection by brother officers.” 28 In contrast, police treatment of Aboriginal people was brutal, often undocumented and legitimised as a response to the violent threat these people allegedly posed. The colonial legal system took white men’s accounts of their intentions and interactions as fact, often citing their ‘high character’ and good intentions and taking at face value claims they were responding to an Aboriginal threat. 29

It is essential that this Commission gives consideration is to the structural role of the QPS in policing racial hierarchies in the past and present. Queensland Police Service is shaped by colonialism, and has played a key role in implementing racist, violent policies from its inception as an institution. Its contemporary racist cultures and practices are well documented30 including in the 2016 judgement in Wotton vs Queensland (No 5) that QPS officers contravened section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination

Act through discriminatory collusion, stereotyping and excessive use of force. 31

3. Murder:

‘She’s just overreacting’

Even the most direct physical harm to women caused by the QPS and the state is minimised or denied entirely. Confronting the reality of QPS abuse is essential to validate victims and find new approaches to DV. Additionally, the QPS and Queensland criminal legal system facilitate a broader culture of impunity for perpetrators of violence towards racialised women. They do this by failing to properly investigate and prosecute perpetrators, especially when these perpetrators are white men.

Racism operates through dehumanisation. The suffering of dehumanised women is not seen as real or worthy of redress. In erasing Indigenous women’s victimhood, the state also erases perpetrators – allowing abusers (including the state itself and QPS) to continue violent behaviours.

As the devastating case of baby Charlie and Ms Tamica Mullaney shows, this erasure of suffering can take place even when police are confronted with a battered, bloody and naked victim of DFV. In this case, the police arrested the woman for assault, with devastating consequences for her baby. An investigation also appeared to blame the woman for the failure of police to act upon 19 the threats to her baby, stating, “it is possible that officers became distracted by [the woman’s] disorderly and obstructive behaviour and did not stop to examine why she came to be naked and injured”.32 Meanwhile, the woman was charged with assault against police and found guilty, though the court congratulated itself by acting ‘mercifully’ in refusing to send her to jail.

It is not that police ‘misidentify’ victims or do not know where to look for signs of DFV. The dehumanising racial stereotypes that police hold outweigh the physical reality of DFV harm they witness. This renders the violence unseeable to them, to the point that police deny victimhood even at its most confronting.

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

Australian police and criminal legal systems are reluctant to properly investigate and prosecute direct murders of Indigenous women. They are more likely to declare them missing of their own accord or somehow responsible for their own deaths.

Even in cases where extreme violence by a white male perpetrator undeniably caused the death of an Aboriginal woman, and a body is present, the Australian policing and criminal legal system positions these men as not fully responsible and/or guilty of lesser crimes. The threshold for viewing white male perpetrators as responsible for murder of Aboriginal women appears extremely high in Australia. The perception of the women as sexually consenting, criminal, dissolute, intoxicated or threatening is regularly used by perpetrators to legitimise their actions and is accepted by police and courts.

The stories of Ms Daley,33 Ms Dann34 and Ms Clubb35 reveal key elements that together form a matrix of disregard for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s suffering. In their investigative practices and individual interactions, they position Indigenous victims as disposable and complicit in their own deaths, frame missing women as wandering off or as threats by perpetrators seeking to avoid culpability for their brutal actions, and the reluctance of authorities to prosecute for murder and/or appropriately sentence white perpetrators. Additionally, of course, police and prisons are directly responsible for killing women through deaths in custody.

The highly regarded Canadian Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls collected extensive evidence over several years.36 It found that Indigenous women are more likely to go missing and remain missing, both because they are subject to higher levels of violence when all other factors are controlled for, and because the police are less likely to fully investigate their disappearance. Testimony collected from the families of missing Indigenous women in Canada show a devastating pattern of this police disregard and inaction, based on stereotypical assumptions about these women as wandering off, drunk, partying, engaged in sex work or otherwise to blame for their own disappearance. Often, the families were left searching for their loved ones themselves, while police told them that their family members had probably just run away.

The National Inquiry found that stereotypes and victim blaming served to slow down or to impede investigations into Aboriginal women’s disappearances or deaths. The assumption that these women were “drunks,” “runaways out partying,” or “prostitutes unworthy of follow-up…characterized many interactions, and contributed to an even greater loss of trust in the police and in related agencies.”37 There is an automatic assumption that Indigenous women are engaged in criminal behaviour, resulting

in excessive use of force by police officers, higher contact, arrest, prosecution and conviction rates, sexual harassment and assault by police officers, and a reluctance to see these women as genuine victims.38

As found in the Canadian Report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, through their direct violence and their support for violence by others, police are directly responsible for the culture of impunity that facilitates DFV and other forms of violence towards racialised women. The QPS are the perpetrators not the protectors of these women – and always have been in this place.

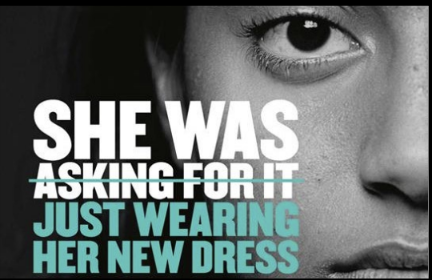

4. Defunding:

‘Let’s stop at the start’

Police powers and resourcing have continued to expand in Queensland in the last year, capping a trend that has been evident for two decades.39 This expansion has been accompanied by a rapid escalation in the rates of incarceration of Aboriginal people, including women and girls. These are not unrelated trends.

There is an assumption contained in the Taskforce’s Discussion Papers, and in mainstream discourse about policing of DFV generally, that police operate as a protective force rather than a threat or source of violence. This assumption is not universal, but rather reflects only the particular interests and experiences of a narrow but powerful constituency: middle-class white people.40 It is clear from the discussion above that for many women, reporting violent crimes does not keep them safe. Police do not prevent violence against women; rather, they become involved after the violence has happened, and then, too often, exacerbate its harmful effects.

Far from being a trauma-informed and evidence-based approach, interaction with police too often leads to imprisonment for women who have experienced DFV, childhood abuse, mental illness, and/or substance abuse. Imprisonment then creates further trauma by isolating the woman from her family and community, as well as routine practices such as strip searching, shackling, and solitary confinement that are known to acutely re-traumatise women and girls with lived experience of violence. Further, once imprisoned, whether sentenced or on remand, the evidence is clear that most women will return to prison, generating massive costs for the Queensland economy as well as an incalculable personal cost for that woman, her family and communtiy.

We do not believe that the role of the police in perpetrating systemic sexism, racism and violence against women and girls can be ameliorated through increasing the numbers of women and First Nations officers, or improving the ‘cultural capability’ of the QPS through greater training. These are ‘band-aid’ solutions that are unable to deal with the state (and therefore racial) violence at the core of policing in this colony and the demonstrable failure of criminalisation as a response to violence. Implementing a ‘co-responder model’ is not a solution we support either; this will primarily serve to reinforce and extend the existing ineffective and inefficient approach. Rather, we must ensure that sexual violence and DFV support services continue to be community-based, independent and ‘on the side of the woman’, rather than (an inevitably subordinate) part of the police response required to pressure women and girls to report violence.

We wish to raise to the Commissioner’s attention two key points. Firstly, that certain women – criminalised and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women – are not helped by police when they experience DFV victimisation, instead, they are often harmed as a result of this contact. Secondly, this issue cannot be ameliorated through mere ‘cultural’ changes within the QPS, such as further training or greater workforce diversity, because it is an inherent feature of an institution built on racism,

sexism, and punishment. There is nothing ‘unwitting’ or ‘unconscious’ about the racialised nature of Queensland policing.

Therefore, decreasing the authority and resources of the QPS in itself is a solution to the violence experienced by racialised and criminalised women. Redirecting this power and resource to community based social programs is also ideal, but we reiterate that the most important factor is the net increase or decrease in police power. Therefore, all solutions considered by this Commission should be evaluated against the following questions:

Does it expand the authority of the state and police over women’s lives, especially over the lives of First Nations women? Does it increase the resources allocated to police in the name of that authority?

If the answer is yes, then this proposal will reproduce and increase violence.

This Commission of Inquiry has the opportunity to break the following cycle: apparent concern for violence against Black women, extension of state authority in the name of protecting these women, increased surveillance and control over these women’s lives, and a subsequent intensification of the violence that was ostensibly the subject of concern. It can do this if it centres the voices of Black women and recognises the racial violence they experience at the hands of the state. We must stop

this violence where it begins and return control to women who experience DFV.

Click here to download a copy of our submission.

_______________________________________

1 ‘No Excuse for Abuse’ (2020) Our Watch, https://www.noexcuseforabuse.org.au/

2 Australian Human Rights Commission (2020) Wiyi Yani U Thangani Report at https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-socialjustice/publications/wiyi-

yani-u-thangani; Human Rights Law Centre & Change the Record (n 1) (2017).

3 Wolfe, P, ‘Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native’ (2006) 8 Journal of Genocide Research 387; A Porter and C Cunneen, Policing settler colonial societies (2020).

4 Jenkins, Keira (2021) Racist police-run Facebook group under investigation, NITV News, 13 July at https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2021/07/13/racist-police-run-facebook-group-underinvestigation

5 ‘Violence Against Women. Let’s Stop It At the Start’ (2022) Australian Government https://www.respect.gov.au/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIi9DqgoX1- AIV0CMrCh1UpgvVEAAYASAAEgJNFfD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

6 Human Rights Law Centre & Change the Record, Over-represented and Overlooked: Thecrisis of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s growing over-imprisonment (2017).

7 J Wangmann, ‘Gender and Intimate Partner Violence: A Case Study from NSW’ (2010) 33 University of NewSouth Wales Law Journal 945; H Douglas and R Fitzgerald, ‘Legal process and gendered violence: Cross-applications for domestic violence protection orders’ (2013) 36(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 56.

8 Human Rights Law Centre & Change the Record, Over-represented and Overlooked: The crisis of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s growing over-imprisonment (2017) 13,17; Stathopoulos, M. & Quadara, A., Women as Offenders, Women as Victims: The role of corrections in supporting women with histories of sexual abuse, (Women’s Advisory Council of Corrective

Services, 2014); D Kilroy, Women in Prison in Australia (Presentation to National Judicial College of Australia and ANU College of Law, 2016).

9 Crime and Corruption Commission (2018) Evidence Given by Darryll Fleming: Transcript of Investigative Hearing: Operation Flaxton Hearing No: 18/0003.

10 Department of Justice and Attorney General (n/d) Youth Detention Centre Demand Management *Name has been changed to protect identity. Strategy 2013-2023, unpublished (Released to the ABC under Right to Information laws) 4; Wordsworth, M. (2014) ‘Qld youth detention centres operating “permanently over safe capacity” and system in crisis, draft report says’, ABC News, 17 September athttps://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-09-17/crime-boom-overwhelms-youth-detention-centres- in queensland/5751540 .

11 Marcia Langton, ‘Two Victims, No Justice’. The Monthly (July 2016).

12 Ibid, p3.

13 Change the Record, ‘Pathways to Safety Report’, Pathways to Safety – Report (2021), p3.; statistics on stranger violence are not adequately collected in Australia, but in the comparable jurisdiction of Canada rates are many times higher. “Even when faced with the depth and breadth of this violence, many people still believe that Indigenous Peoples are to blame, due to their so-called “high-risk” lifestyles. However, Statistics Canada has found that even when all other differentiating factors are accounted for, Indigenous women are still at a significantly higher risk of violence than non-Indigenous women. This validates what many Indigenous women and girls already know: just being Indigenous and female makes you a target”. National Inquiry into

Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women and Girls, ‘Our Women and Girls Are Sacred, Interim Report’ (2017), p.56.

14 Marcia Langton, ‘Two Victims, No Justice’. The Monthly (July 2016).

15 Nancarrow et al (n 4) 79.

16 Queensland Government, ‘Domestic and Family Violence Death Review and Advisory Board – Annual Report 2016-2017 (courts.qld.gov.au)’ (2017).

17 See our earlier joint submission to this Taskforce on coercive control specifically (2021).

18 For a thoroughly documented history of this refusal to accord Black women victim status by the state, police and settlers, see for example Libby Connors, ‘Uncovering the shameful: sexual violence on an Australian colonial frontier’ In Robert Manson (eds): Legacies of violence: rendering the unspeakable past in modern Australia (Berghahn Books, 2017); and Liz Conor, Skin Deep (University of Western Australia Press, 2016); Fiona Foley, Biting the Clouds: A Badtjala perspective on the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, 1987. (UQP, 2020); Jonathan Richards, The Secret War (University of Queensland Press 2008).

19 Smee, Ben (2020) ‘Queensland police: 84 officers accused of domestic violence in past five years’,The Guardian, 3 March at https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/03/queensland-police84-officers- accused-of-domestic-violence-in-past-five-years

20 H Nancarrow et al, Accurately identifying the “person most in need of protection” in domestic and familyviolence law (Australian National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety, 2020), 8.

21 Queensland Sentencing and Advisory Council, Baseline report: The sentencing of people in Queensland (2021) 22.

22 Davis, M. & Buxton-Namisnyk, E. (2021) Coercive Control law could harm the women its meant to protect. Sydney Morning Herald, 2 July 2021.

23 Fiona Foley, Biting the Clouds: A Badtjala perspective on the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, 1987. (UQP, 2020)

24 Libby Connors, ‘Uncovering the shameful: sexual violence on an Australian colonial frontier’ In Robert Manson (eds): Legacies of violence: rendering the unspeakable past in modern Australia (Berghahn Books2017) pp. 33-52; Nicholas Clements, The Black War: Fear, Sex and Resistance in Tasmania, University of Queensland Press, 2014Raymond Evans, Rod Fisher, Libby Connors, John Mackenzie-Smith and Dennis Cryle, Brisbane: the Aboriginal Presence 1824-1860. Brisbane History Group Papers (2020).

25 Jonathan Richards, The Secret War (University of Queensland Press 2008) p.8.

26“In colonial Australia, the early police were modelled on the Royal Ulster Constabulary: the paramilitary police model, which oversaw the 19th century oppression of Ireland” and their 1837 founder Alexander Maconochie was influenced by the Sepoys (a paramilitary force in India financed by the East India Company) Paul Gregoire ‘The Inherent Racism of Australian Police: An Interview With Policing Academic Amanda Porter’ Sydney Criminal Lawyers (online, 11 June 2020) The Inherent Racism of Australian Police: An Interview With

Policing Academic Amanda Porter (sydneycriminallawyers.com.au)

27 Jonathan Richards, The Secret War (University of Queensland Press 2008) p.7.

28 Ibid, p8.

29 As examples: In 1933 Constable Scott was acquitted of chaining and beating to death “a lubra named Dolly” when bringing in fifteen ‘blacks’ for cattle spearing. The Coroner was ‘unable to say if the assault had contributed to her death” and Scott was acquitted with ‘sympathy’ by the judge (Canberra Times 14 and 15 November 1933). In 1895 Western Australian settler Gurriere chained an Aboriginal woman to a verandah post for three days and she died immediately after release. He was fined 5 pounds and the court cited his good character and ‘total absence of malicious intent’. Liz Conor, Skin Deep (University of Western Australia Press,2016) p.149.

30 Most recently by Veronica Gorrie, Black and Blue: A Memoir of Racism and Resilience. Scribe (2021).

31 “The QPS officers with command and control of the investigation into Mulrunji’s death between 19 and 24 November 2004 did not act impartially and independently… [Hurley] was never treated as a suspect, nor promptly removed from the island. The police officers discounted and ignored accounts from Aboriginal witnesses implicating Senior Sergeant Hurley. Incorrect and stereotypical information about Mulrunji and the circumstances of his death was passed to the coroner, while relevant information from Aboriginal witnesses was not passed on… An emergency declaration issued under the Public Safety Preservation Act 1986 (Qld) after the police station was set on fire… was part of facilitating an excessive and disproportionate policing response, including the use of SERT officers”; Judgement in Wotton vs Queensland (No 5) [2016] FCA 1457 (5

December 2016)

32 Corruption and Crime Commission. (2016). Report on the Response of WA Police to a Particular Incident of Domestic Violence on 19-20 March 2013. Report on the Response of WA Police to a Particular Incident of Domestic Violence on 19-20 March 2013_0.pdf (ccc.wa.gov.au)

33 Caro Meldrum-Hanna and Clay Hichens (2016) ‘Lynette Daley’s death: DPP under scrutiny afterunprosecuted killing’ ABC, 9 May https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-05-09/nsw-dpp-under-scrutiny-over-lynette-daleys-unprosecuted-killing/7393368

34 AAP (2020) ‘Man sentenced for killing Aboriginal mother hours after meeting’ NITV, 2 July https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/nitv-news/article/2020/07/02/man-sentenced-killing-aboriginal-mother-hours-after-meeting

35 Isabella Higgins and Sarah Collard (2019) ‘Lost, missing or murdered?’ ABC 8 Decemberhttps://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-12-08/australian-indigenous-women-are-overrepresented-missing-persons/11699974?nw=0&r=HtmlFragment

36 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls; Home Page – Final Report | MMIWG (mmiwg-ffada.ca).

37 Ibid p649. 38 Ibid p632-633. 39 The Honourable Mark Ryan, Record $2.86 billion police budget to boost community safety (15 June 2021) https://statements.qld.gov.au/statements/92396

How can you help?

The Sisters Inside Fund for Children supports children of women in the criminal justice system to choose their own future free of the burdens so commonly felt while their mother is in prison.

#Free Her Campaign

This campaign has been set up by Debbie Kilroy, CEO of Sisters Inside Inc. The funds raised will be used to release people from prison and pay warrants so they are not imprisoned.